The Science4Girls Teacher Guide

Science4Girls is a teaching concept that makes use of project-based learning to foster engagement in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) subjects for girls, ages 12 through 16. This guide describes how to initiate, plan and carry out a learning project focusing on climate change that will help students put STEM-knowledge into context by taking on an important real-life challenge with local presence and global relevance.

- Goal: Foster engagement in STEM subjects

- Target group: Girls, ages 12 through 16

- Domain: Climate change

- Method: Project-based work based in local community

- For more information about the Science4 Girls project - see Science4Girls project website.

Working in teams, students will themselves explore possible project themes, select one they find interesting and engaging, and then plan and execute the project themselves. Teachers provide support and guidance, yet it is important that the students are encouraged to take initiative and find their own path. This allows for them to build confidence in their own ability to take on complex challenges, and respond decisively to obstacles in their way.

In the Science4Girls project our focus was on Climate Change challenges, and thus all examples mentioned here are on Climate change-related issues. That said, it is a flexible learning concept and can be applied for other content domains with a connection to STEM subjects - but should be something with power to engage and excite!

The Teacher Guide is also be available in PDF format - Teacher Guide

As well as a short pamphlet that can be printed out and used as a handout - Pamphlet

Background

Gender and STEM studies/careers

According to several independent studies and reports, girls and women are underrepresented in the STEM studies and careers. UNESCO finds that only 28.8% of the work in the scientific sector is carried out by women. According to the OECD reports, in the OECD countries, only 5% of 15-year-old girls expect to pursue a career in engineering and computing compared with 18% of boys. Are girls less talented than boys to pursue STEM subjects? No, it has been proved that boys and girls have the same level of cognitive abilities required to study and succeed in STEM related field. And yet, when females decide to pursue their interests in the STEM studies, they tend to leave the field at higher rates than men. Maybe there are some cultural obstacles that prevent women from participation in the STEM fields? Interestingly, in countries considered as gender equality champions in Europe, Nordics, the female participation in STEM fields – both in terms of university enrolment and career is the lowest in comparison to other counties.

Why might girls be less interested in STEM?

STEM has been traditionally associated with men and as a male domain and field of expertise. Several studies found that children as well as teenagers associated science with men and depicted scientists to be male. What is most worrisome, this trend has been observed since the 1950s and has not changed much. The authors of most recent studies conclude that despite the increase of women's representation in science over the last decades, children still observe more male than female scientists in their social environments. This STEM – gender connotation is a very significant determinant of the STEM and non-STEM interests as girls (as well as boys) do not want to choose the ‘wrong sex’ profession. This is strongly related to the self-image the girls develop starting in childhood that reflects the gender occupational role segregations.

Bias and embedded stereotypes

The way STEM tasks are designed favours styles and habits of work that are more characteristic to male learners (generally speaking). The STEM area has been claimed to reflect values and interests important to boys and men rather than what would be of girls’ and women’s focus. Boys tend to follow so called agentic goals while girls are drawn more to so called communal goals (Agentic goals are linked to achieving success, whereas communal ones are associated with working with and for other people). STEM-gender connotations have been found to trickle down to education and create the STEM subject biases that favour boys.

The benefits a more balance gender distribution in STEM

Girls’ and women’s equal representation in STEM education and professions is vital from three key perspectives: human rights, science, and development. It goes without saying that girls as well as boys should be able to enjoy equal access to and equal opportunities to study and work in the fields of their choice. Increased female inclusion in STEM is believed to strengthen scientific excellence and enhance quality of STEM outcomes. More women in STEM can contribute to more diverse approaches and perspectives in the field that leads to production of more robust knowledge and development of more effective solutions. There is already plenty of evidence showing women have abilities in STEM fields: i.e., advancements in the prevention of cholera and cancer, expanded understanding of brain development and stem cells. The STEM field needs gender equality and needs a diverse pool of talents and viewpoints to maximize the field potential and leaving out women is a loss for all. Moreover, women’s underrepresentation in STEM education and employment perpetuates existing gender inequalities in status and income – gender pay gap, especially because the salaries in STEM professions currently mostly held by men are better paid.

Climate change, STEM and female values/goals

According to the IPCC Report 2018, the global climate has changed relative to the pre-industrial period, and there are multiple lines of evidence that these changes have had negative impacts on organisms and ecosystems, as well as on human systems and well-being. Climate change has mobilized activism around the world, especially vigorously active are the youth generations gathered for example around the initiative Fridays for Future inspired by Sweden’s Greta Thunberg (https://fridaysforfuture.org/). Young people demand world leaders and national governments to take immediate actions to address the climate crisis. For the girls to get interested in a topic it is crucial that the topic is useful, personally relevant and related to life in and out of school.

The urgency of climate change action and its motivational force

Research on gender equitable science learning finds that introduction of open-ended, real-life problems that address concerns and interests of girls into the curriculum promote gender equity in the classroom and learning. Climate change related issues seem to match exactly the characteristics of the topics female learners would be concerned with and eager to engage in. Therefore, bringing in climate change as ‘problems’ to science classes significantly increases the girls’ interest in learning science. Inclusion of climate change within the scope of STEM redefines the stereotypical STEM’s image as a domain that promotes only agentic values and represents male traits and characteristics. Climate change’ entrance to STEM means the ascent of the so important for the girls’ communal values into the STEM’ realm – working with others and for others, collaborating with each other. Bringing climate change issues to STEM helps bridge the gap between the STEM as science focused on ‘just the facts’ with STEM science that includes ‘also the actions’ - seeks solutions and is action-oriented.

Taking action - seeking solutions

In the face of climate change issues, girls are found to display so-called constructive hope. Girls’ constructive hope vis-à-vis climate change means the girls show a positive and constructive approach towards climate change. They are future-oriented and eager to engage in action and towards solutions identification for the environmental challenges. Girl students recognize the graveness of climate change; however, they genuinely believe they can do something about it. Therefore, offering them an opportunity to work on climate change actions and solution-seeking galvanizes their innate interest and tap into their abilities and potentials.

Open Science Schooling: some practical guidelines

Open Science Schooling (OSS) as a didactical approach to science learning has been experimented with in Europe since 2019 through Erasmus+ project implementations, as a response to the European Commission’s call to “rethink science learning” and to “(e)ncourage open schooling where schools, in cooperation with other stakeholders, become an agent of community well-being; families are encouraged to become real partners in school life and activities; professionals from enterprise, civil and wider society are actively involved in bringing real-life projects into the classroom.

OSS advocates for:

- engaging students in real-life science challenges in the society

- engaging schools and students in practical science collaboration with resources in the local community. These resources take the form of local stakeholders, including research, science, innovation and social resources and stakeholders

- offering students direct participation in epic, immersive and exciting missions that have a relevance for them

- inviting interdisciplinary and cross-class approaches

- offering students with different learning styles a variety of practice-oriented work forms different from traditional theoretical and laboratory-based science teaching

- providing students with the opportunity and resources to develop a different image of what science is and what science could be for them

In this light, OSS supports the meaningful contextualisation of science for students through experiential learning (constructivism) alongside practical, hands-on activities in order to generate knowledge. The ultimate goal is to bridge science learning and students through the practical identification of science as it is used in the students’ environment and context (e.g., local community). This goal is achieved through the engagement in real-life missions with local community actors, which require transdisciplinary support and foster 21st century skills development (e.g. creativity, critical thinking, collaboration and communication, initiative and social skills). In the case of Science4Girls, OSS was deployed through the implementation of local missions related to environmental issues identified by the student teams.

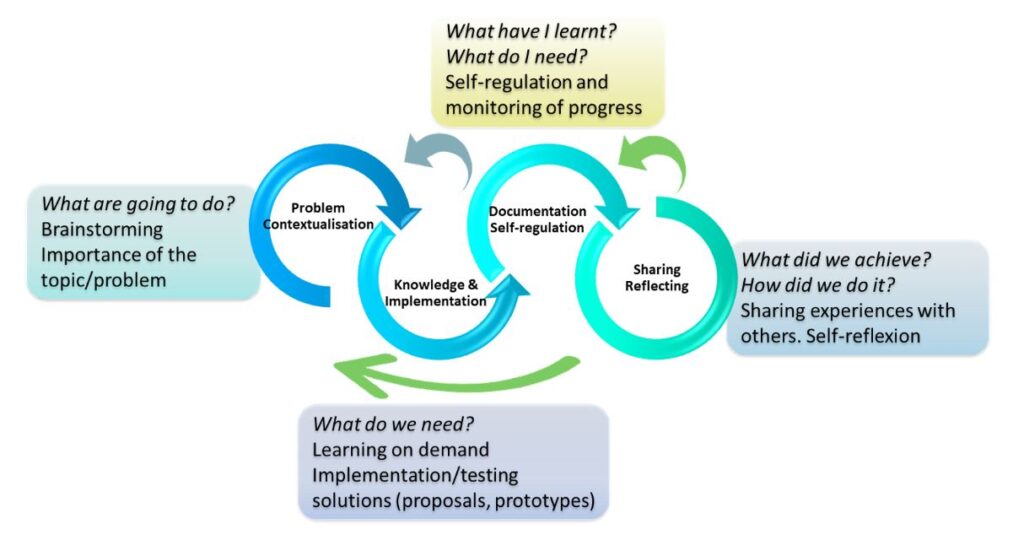

Generally, four interrelated processes have been identified during the practical implementation of OSS: problem contextualisation, knowledge and implementation, documentation and self-regulation, and sharing and reflecting.

How to run student-led climate change learning missions

Preparation - assembling a team

- Assemble a teacher’s team - 2-5 members (or more in you plan to have many project teams)

- At least one STEM teacher, but aim for multiple perspectives by getting teachers from other subject areas involved as well, e.g. languages, art/design, ICT, business, social/political studies.

- Discuss the outer frame for the project among the teachers in the teacher’s team - learning objectives and constraints

- Remember that students choose their own projects and plan their own work. Still, it is important to set a frame for the project by identifying primary learning objectives and the project space’s outer limits - time, feasibility, topical constraints (e.g. focus on climate change, energy supply chains or health issues), external contacts (expected/required).

- Teachers should also consider how different learning styles can be accommodated within the project frame.

- Make sure the frame includes those STEM abilities that the students are expected to work on, and how their performance is evaluated.

- Also consider how to encourage students to use and develop so-called 21st century skills such as creativity, critical thinking, collaboration and communication, initiative and social skills.

- And consider if and how the expression of such 21st century skills can be included in performance evaluation criteria.

- Also consider how to encourage students to use and develop so-called 21st century skills such as creativity, critical thinking, collaboration and communication, initiative and social skills.

- The teacher team should also consider and discuss the role of gender for STEM-learning in this type of setting.

- Discuss guiding principles for how the teacher’s team will support and guide the students, i.e. providing active guidance and support, but avoid instruction and control.

- Develop consensus within the teacher team regarding the outer frame, guiding principles and working process to coordinate their efforts and the way they communicate with and guide the students. This is especially important in a multi-disciplinary team with members, who might be less used to working together.

- How much time to spend on preparation depends on how detailed the outer frame needs to be, which in turn depends on what the learning goals are and how the project work is expected to integrate with other learning activities. But don’t overdo preparations. It is difficult to cover everything, and some details will have to be discovered - and appropriately responded to - when the project is underway.

Introducing the Science4Girls learning concept to students

- Introduce project-based learning to the students

- Stage opening event that introduces the focus and outer frame of the project and provides inspiration

- Make sure students are aware of the type of learning goals concerning STEM-knowledge that they are expected to include/learn/develop during the project work.

- Assemble project teams

- Recommended group size: 4-5, ages 12-16

- Present/suggest and discuss with students possible contacts - local authorities, companies and individuals.

- Help students learn how to approach local contacts - to think about who to contact, what to say, what type of information or collaboration one seeks and so on.

- Finding, appropriating and working with local communities' resources:

- How to identify, make contact, understand, take action in collaboration… [Note to self (Martin): important point, make sure the experiences of the partners is represented]

Generate and select project alternatives

- Get teams going by exploring local opportunities

- Help establish connections, also encourage students to use their own or make new connections (under teacher supervision).

- Students are tasked with identifying project alternatives that are interesting and engaging to them

- Using ideational techniques such as brainstorming.

- Identified problems are put into context, but examining their surrounding setting and connections - problem contextualisation.

- …and by exploring their surroundings and talking with the people they find there

- For each identified alternative: explore challenges, describe expected outcomes, identify benefits and discuss the importance of the topic/problem - at the local level, and the global level.

- Projects are expected to produce some type of positive change or impacts (not only describe or evaluate)

- Teachers supervise and make sure that the projects align with learning objectives and keep within the established outer frame, including STEM learning goals.

- Students compare alternatives and select the project they wish to pursue

Teachers provide support and guidance, yet it is important that students make the choice themselves. This to foster both engagement in the chosen subject, and support the sense of self-sufficiency.

Plan and execute - student-led, teacher supported- Iterative in nature

- Students are expected to plan their own work

- Students set their own goals and plan their work. Students should be encouraged to explore alternative directions, and when settling on a specific way forward to avoid planning too far ahead, as this can hamper their ability to make appropriate course corrections when reacting to developing circumstances.

- Teachers provide support and make sure that identified goals are aligned with learning goals and other aspects of the project’s frame, but it is important that the students are allowed to find their own way and given room to experiment.

- Responding to the complex real-life demands

- Students should be encouraged to monitor the progress continually and use self-regulation to re-evaluate their plans, and not to be afraid to adjust both goals and work methods to take advantage of new experiences.

- Experimenting and testing solutions in realistic settings should be an integrated part of the work effort. This to gauge the credibility and value of generated proposals and prototypes.

- Teacher’s help students gain balance between just moving forward, and moving forward in an interesting direction - with the experience accrued at each step illuminating the way forward. It is important to help students deal with the uncertainty of project challenges that are not predetermined, but need to be discovered, understood and dealt with as they are encountered.

- Document the work

- Students are expected to document the work they do - with notes, pictures, video and other materials.

- Teachers should remind the students to document and keep the documentation in order.

- Identify the role of and need for STEM knowledge

- Teachers and students jointly identify STEM knowledge and skills required to work effectively and efficiently with project challenges.

Teachers help students address encountered knowledge gaps in the project process, and help students fill those gaps and apply gained knowledge appropriately - learning on demand.

Towards the End goal

- What goal?

- Where the end goal is and what the end goal is, is something that needs to be discovered. It will have been (positively) constrained by the initial frame and shaped by careful nudges along the way, but should also include elements of surprise. By encouraging students to be both opportunistic and mindful in their selection of routes, the project will move towards interesting goals that reveal themselves at the end.

- When to finish?

- When the project concludes is often determined by outer constraints - such as time available or a predetermined deadline. Students should be encouraged to be aware of such constraints, but not to let them dominate their decisions on direction and goals, to make sure that the goal is pursued because it is interesting rather than convenient.

- Documenting the journey and the destination

- OSS promotes storytelling as an intuitive yet powerful means of describing both results and process.

- Teachers should encourage students to write and record during their journey, and then reflect and express their reactions to where they ended up. Encourage students to use other means than writing to make stories come alive - video was used to great effect by many groups in our project.

- Reflections should include both results and gained insights in relation to the project they have pursued; personal and group-level insights gleaned from the experience of running a project such as this; and how this experience has affected their understanding and perception of STEM subjects and how this, in turn, has affected their attitude towards and image of science in general.

Students should also be encouraged to reflect on what doing science as a female is like, and how the female perspective carries potential to expand and develop what science could be.

Spread the message

- What did we achieve? How did we do it?

- Reports and reflections on the journey and the destination are valuable in their own right - as testaments what one has produced and what one learnt along the way - but their real value potential is revealed when shared broadly and generously with others.

- Encourage students to share their experiences via posts on social media, publishing to the web, holding presentation events, and just talking with people they happen to meet, or intentionally seek out.

- Sharing is valuable both for the recipient and for the sender. The recipient learns new things and broadens their perspectives; students receive affirmation and feedback, including - hopefully - feedback which questions and challenges. This promotes additional learning opportunity by providing contrast and adding nuance.

Science4Girls missions in the wild

Examples of climate change missions from the project

- Ins Vilafant

- Pasvalys Lėvens

- Secondary School Gheorghe Titeica

- Srednja Elektro- Racunalniska Sola

- Växjö Internationella Grundskola

The environment is all around us! To find out more about how climate already is affecting us we turned our eye towards the local Manol river and the surrounding Empordá wetlands. We took water samples from the river and also investigated plant life and the river sands. In the process we found out about things like how salt forms crystal formations; the effect of water temperature on aquatic life in the river; and how carbon dioxide concentration in the water and sandbed is affected both by local geology and global climate effects. We interviewed a well-known TV meterologist and got some useful tips on what can be done to slow or even reverse the effects of climate change. And with our new-found understanding of both problem and solutions, we reached out to others through articles produced by the students and published in a local magazine and a newspaper.

We also participated in a “plogging” event - cleaning up nature by removing plastic bottles and other waste - part of the Clean up Europe initiative! (“Plogging” is a combination of jogging and the swedish word “plocka upp” - picking up, and consist of jogging around and picking up litter - with special focus on plastics).

- What: Climate change effects on local river

- Where: Manol river and surrounding wetlands in Empordà

- How: Field trips, research, interviews, experiments

- Sources: Metereologist, Biologist, Ecologist

- Local/global: Understanding how important water quality is for local flora and fauna, and how climate change affects water quality everywhere.

- Subject focus: Chemistry and Biology

We use a lot of paper, cardboard and textiles in our lives. Some of it gets recycled and is used in new similar products, but some ends up on garbage dumps, is burnt or - worse case scenario - ends up in nature or in the sea. Too often we don’t think about what happens to the shoe box we got our new sneakers in, or the t-shirt that is nearing the end of its run.

This was the starting point for our mission and we decided to give new life to shoeboxes, toilet paper rolls and old textiles by re-making them into pieces of art! The lids of shoe boxes became beautiful paintings, toilet paper rolls were transformed into figurines and toys, and left-over clothing was refashioned into artist materials.The students explored the problem area, identified challenges, and brainstormed solutions, making use of their curiosity and creativity at every step. Curiosity in wanting to understand the situation - starting locally but also considering the global scale of the problem. And creativity both in the generation and development of possible solutions, and in the Art created with left-over paper and textiles.

The exercise was both fun and thought-provoking, bringing attention to the important issue of reducing waste locally and globally and how what we do today affect the future, not only for ourselves but for coming generation - and making this stick in the minds of the students themselves as well as the recipients and viewers of the resulting Art.

- What: Creative re-use of paper and textile waste

- Where: School setting

- How: Using paper and textile waste as material for creative works of art

- Sources: Peer Power

- Local/global: Re-use through re-purposing cutting resource footprint in half

- Subject focus: Ecology, Art

Water is truly the essence of life - and due to ongoing climate change, water is unfortunately something of diminishing supply in our country of Romania. Droughts are getting longer and more severe, resulting in dried out soil and dwindling crop yields. We researched the issue by reading up on how climate change is affecting the water supply, and then performed lab work to get into the details of its actual effect on soil quality and understand how it affects plant life.

We also visited a research institution where they are experimenting with different techniques for growing crops in dry and sandy soils, as well as trying out alternative crops that manage better with the type of environment that climate change is producing. We need to sound the alarm and do what we can to combat climate change globally, but we also need to adapt locally to changes that are already happening around us, for example by changing what crops we grow and how we grow them. Knowledge lets us both understand what is happening, why we need to take action, and what we can do - right now and perhaps in a future role as a scientist/ activist!

- What: Water shortage’s effect on plant growth

- Where: Research station

- How: Research, Field work, Lab work

- Sources: Research-Development Station for Plant Culture on Sands in Calarasi

- Local/global: Climate change induced water shortage and the need develop alternative cultivation practices.

- Subject focus: Physics, Chemistry

We are surrounded by tech - computers, telephones and all sorts of gadgets. Tech grow old fast and our new phone gets replaced every couple of years, or even every year. What happens to all the discarded stuff? The new phone is made out of the same stuff as the newly obsolete one - including many valuable and rare metals and minerals. So how can these materials be re-used? Perhaps the phone can be refurbished and find a new owner with lower demands on processor speed, screen size and camera resolution? e-Waste companies collect electronic waste, separating it into the re-usable and re-cyclable, reducing the waste portion of it to a minimum. Working stuff is resold, either locally, or shipped to a different part of the world. By salvaging the re-usable and collecting the re-cyclable, the ecological footprint can be reduced considerably. By researching the re-use/recycling chain, the students came to appreciate how individual habits in aggregate impact the world. And, consequently, how one can develop new personal habits to avoid being part of the problem. And by encouraging others to do the same, break the cycles of linear economies (take-make-consume-dispose) and foster a thoughtful attitude and long-sighted mindset to better take care of the planet’s limited resources.

- What: e-Waste - recycling/reuse of electronic devices - and circular economy concept

- Where: Recycling company

- How: Research, Raising awareness

- Sources: ZEOS (NGO), Snaga (Recycling company)

- Local/global: Local recycling to foster global sustainability

- Subject focus: Economics, Sustainable ecology, ICT/Technology

We have focused on the empowerment aspects of having the girl teams choose their own topic and organise their own work. The girls took inspiration from watching films and documentaries on climate change. After exploring a number of different issues they decided to focus on food waste - a local challenge that has global relevance, as well as urgency in a world that needs to become better at managing its limited resources. The girl teams performed research to find out more about food waste - the extent of the problem, and its impact on, and connection to, climate change. They investigated different measures, such as producing educational materials - colouring books, games and videos aimed at younger children and educating them about the problem with food waste; and a digital app that would provide school children with more choice for what they will have for lunch.

The educational material was tried out with younger children at their school. And to investigate the effect of increased choice on amount of food waste, they performed a practical experiment at the school canteen. Food waste was reduced by a considerable margin. They also reached out to the provider of the digital school platform to find out more about the practical steps on how an app idea such as this can move from idea to proof-on-concept, and then to development and finally deployment.

- What: Food waste

- Where: School cafeteria

- How: Local observation, research, interviews, measurements

- Sources: Cafeteria personnel, Tech company executive

- Local/global: How food waste starts with the individual, yet has affects in aggregate on the whole world

- Subject focus: Nutrition, Ecology, Resource efficiency, ICT and app development

Testimonies from participants

- Participating female students

- Participating teachers

- Experience-based recommendations

Presentation of what the students thought about their experiences and how it has affected their view on science, science-in-practice and being a female practitioner in science. Could also include things like local/global perspective, project-based learning, meeting people from other countries.

- Each school presents testimonies from female students…

- Ins Vilafant: Boys and girls participating in this european project have different opinions about fostering science to girls. Girls have been really involved in the project, they have certain curiosity and the fact that all the missions were very practical helped their motivation. Some of the girls have expressed their willingness to continue studying science in the future and study a degree related to STEAM. This european projects have helped them to relate their formal education to their real life and they have been able to connect knowledge to everyday problems. Boys think that it is interesting to have girls in science degrees because the way they see things may be different and this is enriching.

- Växjö Internationella Grundskola: Through the project the students engagement and interest have varied. Clara said: “In the beginning of the project it was not clear for me what was expected of me and where we were heading”. Sewar said: “In the second part of the mission it became clearer and then the project started to be important and fun.” Sanna continued: “When we had decided on what climate issue to focus on it was easier to see the Science in the project”. Nicolina said: The best part of the project was to meet up with everyone in Portugal. Lujian added: “I really enjoyed meeting the other students and discussing stereotypes with Joanna.”

- Each school presents testimonies from the teachers…

- Ins Vilafant: According to the teachers, girls have more curiosity about the reason why facts happen the way they happen, they are also are more mature and responsible and think that what they are doing is going to make a difference. Girls, normally, are also more conscious of the climate change and the negative effects it may have in their future life. The only problem is that they are also very self-demanding and some times, the results they get are not the expected ones and that seems to get more frustrated. On the other hand boys are more childish and enjoy the process of the practical experiments but they don’t really know what to do with the results and they are not normally so focussed on the tasks afterwards.

- Växjö Internationella Grundskola:

Kristin: It has been fun to see the girls grow with this project but also challenging as a teacher to get the project manageable and keep the girls motivated and interested. Hanna: This has been a challenging but fun and meaningful project. Even though it was challenging in the beginning it has been great to watch the girls develop and grow as scientists.

Experience-based recommendations on how to tackle challenges, difficulties and obstacles in open science schooling and climate change missions

- Each school presents their views…

- Ins Vilafant: It is true that we have been living a very difficult situations with COVID 19. During many months some of the students have been under the lock down and this has been a problem for the project due to the lack of continuity. Another challenge has been the few possibilities we have had to contact life with experts. Time is another factor that we have realised it could change in our school in future edditions because maybe with more time students would have been able to achieve greater things. We are happy though that students have been able to connect their knowledge to real life and share it with other european countries.

- Växjö Internationella Grundskola: We found that narrowing down our mission focus and setting a clear goal really improved our girls’ engagement in the project and that they then more easily could understand the purpose and the parts of the work that we did. The mission also needs to be on an appropriate level and a lot of teacher guidance is required to reach goals within the project. Open science schooling requires a lot of time, time that we did not always have. It was also hard to get companies and the society involved in what we did.

Things to consider…

Opportunities, challenges and pitfalls

By letting students explore and choose projects that are important to them - and then plan, run and adapt to the challenges they encounter - students grow in their sense of agency being able to make a difference and confidence daring to make a difference. They learn to handle the uncertainty inherent in any project where the goal is - at least in part - discovered along the way. This builds confidence and inspires young people not to shy away from difficult challenges. Of course, students also need help and support. Here is a fine balance between asking too much of inexperienced learners traversing unknown territory, and the empowering experience of being allowed to chart one’s own way. Teachers provide the infrastructure for OSS by setting starting points, establishing frames, and helping out, but they also need to dare to take a step back to allow students to try things out, as well as making - and learning from - mistakes along the way. This balance between support (good) and control (less so), and guidance (good) and instruction (less so), should be considered when setting the frame at the beginning, but is also something that needs to be constantly monitored and re-evaluated to measure progress and keep students on the right side of feeling challenged and empowered and away from feeling lost and overwhelmed.

Agency - being able to make a difference | Confidence - daring to make a difference

Girls may have had bad experiences and been made to feel out of their depth or in the wrong place when taking on scientific or technological challenges. Although the title Science4Girls might seem to suggest that this learning approach is only for girls, this is not the case. It is perfectly possible to run Science4Girls projects with mixed teams - in fact, several of the teams in our project had both boys and girls. Yet it is very important that teachers strive to establish and maintain a working atmosphere in which girl participants do not feel encumbered or judged by expectations and preconceived notions of what girls should be interested in, or what they can do. The teacher team should prepare for this in setting the frame for the project, and also be on the look-out for signals that girls might be held back directly or indirectly, and from within project groups, or in contacts with outside partners or contacts.

Leveling the playing field for Girls

Students are encouraged to choose projects that have a local presence, yet have global relevance. Once projects get started and students get into the nitty gritty details of what is going on in their immediate surroundings and with their project, they might lose track of this connection. A careful nudge or just the occasional reminder to consider the larger context, can help student teams apply insights from the project to better understand international issues, and conversely, draw inspiration from the greater scene to put their own efforts into perspective. The local/global perspective is something that should have a presence in every stage of the project work - from exploring choices, selecting a project, working on the project, and considering the implications and consequences of what one has learned and done. One positive way of broadening one’s outlook can be seeking collaboration partners in other parts of the world. The Science4Girls project drew both inspiration and motivation from their contacts with teams in other countries. Traveling to meet in person may not be possible for your school/students, but consider establishing connections with schools in other parts of the world using video conferencing services to interact and work together (for example via Erasmus eTwinning initiative).

Act Locally | Global Perspective

Consider how the students' performance is to be evaluated. For the type of open-ended, exploratory project work the students are encouraged to perform, it can be difficult to set specific subject-based learning goals. And equally difficult to then measure their attainment, especially when work is carried out in groups, where tasks are expected to be unequally distributed among team members. Consider therefore if student performance might be evaluated at the group level, and in a holistic manner with less separation into traditional subject categories and more focus on dynamic aspects such as agility and responsiveness. Skill in working together with others, and being able to react and respond to the demands of a dynamic real-life situation - as a group - are important life-skills to have. This should be reflected and rewarded in the evaluation of student performance. Such a shift towards a more holistic evaluation model might present challenges in relation to school curricula and existing subject-centric learning goals, but it is an important shift to make to promote the type of integrated, in-context skill set required to tackle the important challenges of today and tomorrow.

Impactful learning

real-life issues are messy and unpredictable. Students will make mistakes and have to deal with adversity along the way. Getting to choose one’s own project fosters motivation and generates drive to push through the rough patches. It also helps forge strong memories of the experience, with what was learned firmly placed into context. This resulting rich memory trace makes it much easier for the individual to later on trigger that connection when encountering similar situations. Moreover, since an important part of that original experience will have been reacting and responding with agility and creativity to the demands of the situation, the stored knowledge will likely retain a lot of that flexibility. This, in turn, will make it easier to re-apply that knowledge not only to those rare perfect matches, but to a range of settings and situations. These are skills adapted to the real-life, and skills that are retained over the long-term due to their holistic character and engaging nature.

Learning that matches real-life challenges

Working on important challenges is also a strong motivational factor. Environmental concerns in general and climate change specifically are areas that engage and excite at a personal level - especially when seeing the local connection, but it is the global and historical significance that elevates the learning experience to an empowering one, and pushes students to continue taking interest and taking action. And, most importantly, the experience of having used STEM subject knowledge and know-how to understand both the problem and use it to work on solutions in a real-life context, produces both ability and drive to take on similar challenges in the future. And this, for some, may lead to a career choice to make solving difficult and important problems with the aid of science a life mission.

Making a difference

Good luck! Remember a guide is no more valuable than the person using it! Be mindful, be flexible and help the students adopt that same mindset. And never stop learning - this applies equally for students and their teachers!

Teaching materials

Below you will find various teaching materials that you can use to introduce your students to the learning concept Science4Girls, as well as the topic of Climate change prevention and Gender roles in science.

Getting started

Work progression

Climate change

Open Science Schooling resources